#171 Tokyo in a Loop: 100 Years of the Yamanote Line

How the most iconic railway in Japan came full circle — connecting past, present, and future.

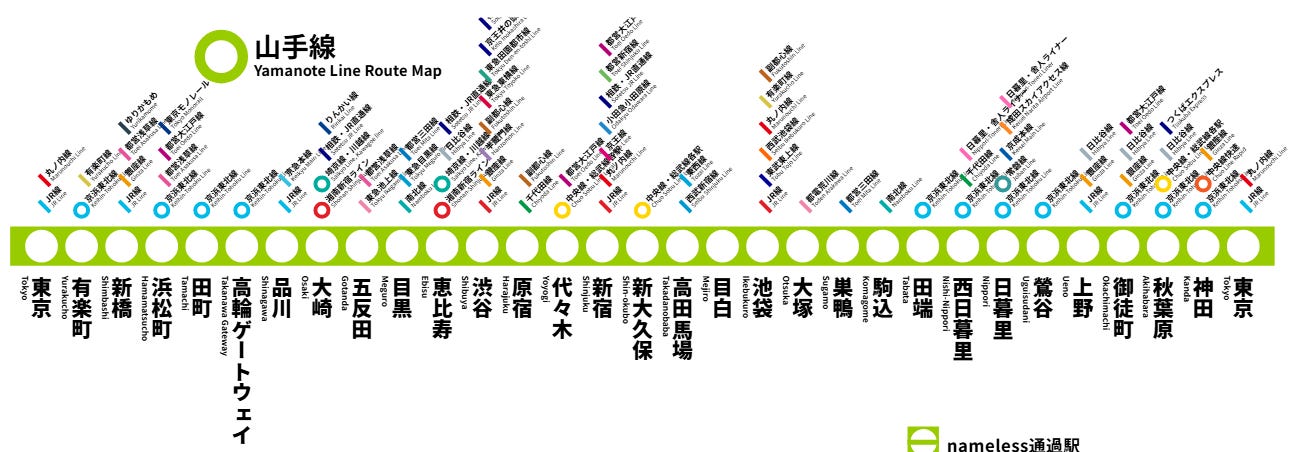

The JR East–operated Yamanote Line — a 35-kilometer circular route connecting 30 stations across central Tokyo — is arguably the most recognizable railway line in Japan, familiar to everyone from local commuters to international visitors.

Yesterday, November 1, marked the 100th Anniversary of the completion of the Yamanote Line as a complete loop. It was a milestone that resonates not only with railway enthusiasts but also with countless Tokyo residents and travelers who rely on it every day.

This week, I will take a brief look back at the Yamanote Line, which has a fascinating history, and explore how understanding this iconic route can enrich both daily life and travel in Tokyo.

Brief History

The story of the Yamanote Line mirrors Tokyo’s own evolution — from a modest capital to a global metropolis. You can trace the development through three key stages:

Stage 1: The Beginning — Shimbashi to Kanda (1885)

The line began in 1885 as part of the government-operated Shinagawa–Shinjuku–Akabane route, linking with Shimbashi. Initially intended for freight and military use through what was then a rural “Yamanote” area (literally “foothills”), it was far from the busy commuter artery we know today.

Stage 2: Integration with the Chuo Line

As Tokyo expanded westward, the demand for commuter transport surged. Connecting the Chuo Line with Tokyo Station via Kanda and Shinjuku in the early 20th century created the backbone of a true urban rail network — linking workplaces, residential districts, and emerging suburbs.

Stage 3: Completion of the Loop (1925)

On November 1, 1925, the final section between Kanda and Ueno opened, completing the 35-kilometer circle. For the first time, trains could operate continuously around central Tokyo — a milestone that symbolized Tokyo’s modernization and connectivity.

Modernization and Urban Growth

From the 1920s onward, the Yamanote Line evolved alongside Tokyo’s modernization. The rise of private railway companies — Tokyu, Seibu, and Odakyu — fueled enormous commuter demand at interchange hubs such as Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, and Shibuya. These stations grew into dynamic sub-centers, transforming Tokyo from a single downtown core into a multi-core city.

Electrification, new rolling stock, and mid-century upgrades cemented the reputation as Tokyo’s urban circulatory system — a loop that keeps the city heart beating.

The Importance of the Yamanote Line — The Pulse of Tokyo

The Yamanote Line is more than just a railway; it is a circulatory system, moving over four million passengers daily in Tokyo and connecting the primary business, shopping, and entertainment districts.

Because of its loop structure, the line doesn’t merely connect point A to point B — it forms the spinal ring that binds the city together. From the fashion culture in Shibuya and skyscrapers in Shinjuku to museums in Ueno and electronics and anime in Akihabara, nearly every defining face of Tokyo lies along its track.

Economically, it has shaped urban growth for decades. Property values and commercial activity around its stations remain among the highest in Japan, making the Yamanote Line a literal engine of development — often called “a city within the city.”

For daily users, its strength is simplicity and reach: wherever you choose to go among its 30 stations, you will arrive in about 30 minutes, without complication. You only need to decide — clockwise or counterclockwise.

For visitors, it’s the most convenient way to explore Tokyo: a single, continuous line connecting landmarks, neighborhoods, and contrasts — a moving window into Tokyo life.

In short, the Yamanote Line isn’t just a loop on a map — it’s the lifeline that defines how Tokyo moves, grows, and lives.

Did You Know?

Did you know the Yamanote Line loop is about 34.5 kilometers long and takes just over an hour to complete — meaning you can circle central Tokyo in the time it takes to watch a movie?

Did you know there are now 30 stations, after the addition of Takanawa Gateway Station in 2020 — and every one connects to at least one other JR or private railway?

Did you know trains run every two to four minutes in both directions, inner (clockwise) and outer (counterclockwise), so you never have to plan far ahead?

Did you know that if you accidentally fall asleep, you will return to your starting point in about an hour — a real-life “commuter’s nap circle“?

Did you know the line links five key centers in Tokyo — Tokyo, Ueno, Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, and Shibuya — what locals often call the “Golden Loop”?

Beyond these facts, the Yamanote Line hides a few charming stories and unsung details. Let’s explore some of them next.

Hidden Interesting Topics

The Perfect Loop Myth

Many imagine the Yamanote Line as a perfect circle, but it is actually slightly oval-shaped, curving toward Tokyo Bay to the east. The “loop” image has become symbolic — representing the seamless connectivity — and remains one of the most recognizable icons in Tokyo.

Osaki Station — The Hidden Hub of the Southern Loop

Not a tourist hotspot, yet a vital operational core. Osaki Station is where trains are dispatched, stored, and maintained, and where the Saikyo and Rinkai Lines meet. Around it, a quiet but modern business district has emerged — showing how the Yamanote Line drives Tokyo’s urban growth even beyond its famous centers.

Tips for International Travelers

For international visitors, the Yamanote Line is more than just a means of transportation — it’s a gateway to everyday life in Tokyo.

Because of its loop, you can easily reach most major districts without complicated transfers. However, for cross-city trips (e.g., Ueno to Shibuya), subways may be faster. Tokyo Metro offers 24/48 and 72-hour passes — ideal for flexible sightseeing.

Use Suica or Pasmo cards for convenience, and rely on the Yamanote Line especially for smooth north–south travel along the western corridor.

Avoid peak hours (7:30–9:30 a.m., 5:00–7:30 p.m.) for a comfortable ride. The congestion of the Yamanote Line is unimaginable during peak hours.

Be cautious at Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Ikebukuro — the busiest hubs, often crowded and under renovation. The renovation and narrow platforms may sometimes limit the number of passengers on platforms.

Remember that both directions lead to your destination on Yamanote Line — decide which direction to take.

The Future of the Yamanote Line

As Tokyo continues to evolve, so does the Yamanote Line. JR East is investing in smarter, greener, and more accessible operations. The latest E235 series trains feature energy-efficient systems, larger windows, and digital onboard information. JR East is also upgrading with AI-assisted management and barrier-free designs for universal access. New connections — especially around Shinagawa and Takanawa Gateway Station — are reshaping the southern loop into a model of “next-generation urban mobility.” Sustainability remains a core goal: regenerative braking and energy reuse reduce environmental impact, while multilingual digital tools make travel easier for everyone.

A century after completing its loop, the Yamanote Line remains not a relic of the past but a symbol of Tokyo’s innovation and continuity. This circle keeps the city moving forward.

Wrapping Up — A Circle That Never Stops

From its humble beginnings in 1885 to its 100th Anniversary as a complete loop, the Yamanote Line has always been more than a train — it has been a mirror of Tokyo’s rhythm and resilience. Every station tells a story; every ride connects past and present. Whether you are a commuter, a visitor, or simply someone watching the green train glide by, the Yamanote Line reminds us that Tokyo never stands still — it keeps circling forward.

Happy 100th Anniversary to beloved loop!

Your note about the 1 hour nap potential made me think someone has to have based a short story or even a novel on that fact!

Thank you for this excellent post packed with lots of useful information. Although I hardly ever visit Tokyo now, I fondly remember riding the Yamanote Line when I spent a year there as a scholarship student in 1998/99.